What it is ain’t exactly clear. I have a distinct memory when I was young of my sister and I mockingly singing the chorus to Buffalo Springfield’s song For What it’s Worth during the car ride home from school. It was Grandma’s day to pick us up, and her golden 1980 Mercury Zephyr car only had the radio available. When it wasn’t tuned to KCBS (and that was a rarity), it was on an oldie radio station. We half-giggled, half-sung out the chorus in loud, silly voices as we exited the car and came up to the front door. We thought that it was funny that an ‘adult’ song would urge children to stop, identify a sound, and then look around.

Now Grandma put up with a lot of silliness. As a school teacher and having had six children to look after herself, she was pretty used to the antics of kids. But on this particular occasion, Grandma wasn’t having it. As we were about to go into the house, she deplored to us, Stop that! That’s a serious song! My sister and I, taken aback by Grandma’s unusual outburst, promptly shut our traps but gave each other a sideways smirk. We didn’t know the meaning of the song, and we certainly didn’t understand Grandma’s concern that day.

It obviously wasn’t until I was older that I was fully able to grasp the meaning of that incident, that I was able to understand Grandma’s gravity. As a history minor in college, I was afforded the time and space to get my head around ‘modern’ American history. And the sixties always seemed to fascinate me the most because there seemed to be so much going on: the fashion, the music, the muscle cars, the social progress. And the Vietnam war.

For all the glory and invincibility American history establishes, the Vietnam war seems to be a glaring blemish in our timeline. I’ve seen many movies (Full Metal Jacket, Born on the Fourth of July, Platoon) and read some books (my favorite is Matterhorn) on the matter. And my understanding of the war itself, the reasons for spending $120B, for sending 2.1M soldiers, for the 58,000 that didn’t come back alive, for ignoring the post-war effects neither at home nor abroad, all seem categorically unAmerican to me. So coming to Vietnam, especially Ho Chi Minh City, was particularly enthralling for me. There are always two sides to every story, and I had to see for myself.

But before we could get into any of that, we had a chance meeting with some old friends. I’m not a huge user of social media, but I am fond of Instagram. And Shiv happened to notice one of our old-timey Google friends (circa ’08!) who had gotten married and moved to Singapore were in Saigon! We reached out and made last minute dinner plans – which was amazing! Thank you Instagram for uniting some old friends. We miss you Jenn and Nick 🙂

Củ Chi Tunnels

The next balmy morning, we headed out with our hired tour guide, Nguyen Nguyen, whose first and last name is supposedly pronounced slightly differently though our untrained ears were never able to discern the difference. It’s a 45 minute drive from Ho Chi Minh City to the Củ Chi tunnels. So we had a lot of car time together, which included a hearty discussion on the best pho places and a curiously unprovoked 30 minute drop off at a handicapped handicrafts area where they pressure you to buy goods to support the handicapped artists. We did give it an authentic look, but ultimately decided against purchasing anything. Don’t judge.

The Củ Chi tunnels are an entire network of tiny underground tunnels that sheltered the Viet Cong (and their weapons) during the war. In twenty years, there were 120 miles of hand-dug tunnels that first started during the first Indochina War with the French in 1948. By the time of the Second Indochina War (the Vietnam War to you ‘Mericans), these tunnels were quite complex and had 3 layers, up to 30 feet underground.

Our day started out with a funny propaganda film in an underground hut. It told of the happiest place on earth, Củ Chi, being destroyed by the most evil people on earth, the Americans. We walked out of there feeling sheepishly awkward and silently ostracized, akin to when you take the last piece of office cake and everyone knows you did it.

Our tour continued with a look at an actual, preserved Củ Chi tunnel. It was much too small for Shiv to fit, but I could have done so if I hadn’t been afraid of what was lurking inside. Our guide warned of scorpions and I had read that poisonous centipedes made their homes in the tunnels, as well. Plus, I could see that there were some worms wriggling around in there.

What made this field trip especially eerie was the fact that there was a firing range in the place. You can, for a fee, fire automatic and semi-automatic weapons. The whole time as you are walking around, you are hearing loud gun shots. Seeing the tiny tunnels and the swimming-pool-sized craters from the B-52 bombs coupled with hearing the gunshots, it’s not hard to imagine the panic one must have felt during the war. In fact, it was really hard to escape it.

In addition to the tunnels, the tour also provides insights into daily Vietnamese life in the village. We ate raw tapioca dipped in a dry dip of sugar, salt, and pepper. It was…dry. We saw how rice paper and rice wine were made. We even learned how the Viet Cong tricked the Americans by wearing their sandals backwards on their feet, making it appear that they were heading north when in fact they were traveling south.

Another trick that the Viet Cong utilized were booby traps. There were at least 10 different kinds that they devised. Each one was essentially a hole dug in the ground with some sort of sharpened bamboo spike apparatus within it. Cover the hole with leaves and other foliage and you have yourself an indiscernible trap. Since bamboo spikes wouldn’t necessarily kill a soldier, they made sure to dip the spikes in dirty water so as to cause infection when piercing the skin. This is a decent video if you’d like to see more on the booby traps (you can even hear the gunshots firing in the background.)

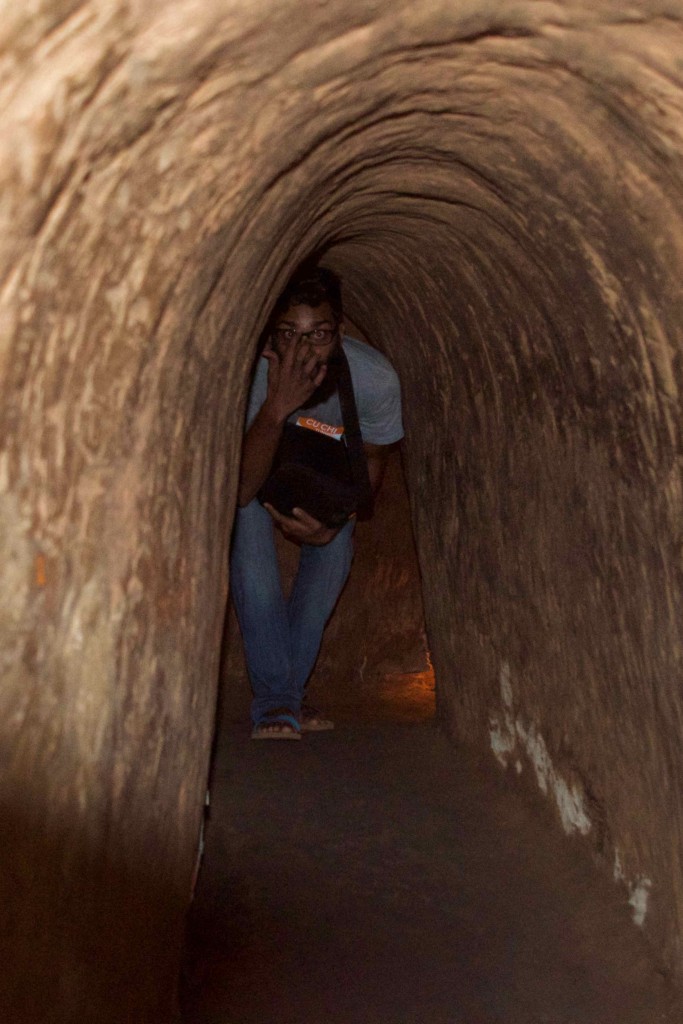

Finally, our tour ended with an actual crawl in a tunnel. This particular tunnel was made slightly larger for Western people to fit. As I squatted and worked my way through the tunnel, I imagined myself during those times. It was dark, it smelled musty, I didn’t know where I was going or how long the tunnel was, I was getting dirty, the air was hard to breathe, my knees started to ache – all of these things in a 5 minute tunnel crawl. To think of the people who lived down here for days, weeks, months, at a time! It seemed almost impossible. And maybe it was…an estimated 48,000 Vietnamese died in the tunnels either through disease (malaria being the most common), snakes, flooding, poor ventilation, and attacks from American tunnel rats (specially trained soldiers who went in the tunnels to attack).

As I said before, I didn’t go into the actual tunnel. While I didn’t want to ruin our Vietnam trip with an emergency visit to the hospital (I mean, I had already 50% ruined Luang Prabang), I couldn’t help but think that if there were bombs being thrown at me in Cu Chi, I’d sure as hell get my ass in that tunnel.

War Remnants Museum

The propaganda film in the Củ Chi tunnels was only the tip of the iceberg for the peculiar heaviness, the inadvertent ignominy of simply being American, that we’d drag around with us throughout the entire day. The War Remnants Museum is Vietnam’s exhibition hall for exposing war crimes. Throughout the years, it has had many names, with each version less and less blatant as US and Vietnam relations improved: first Exhibition House for US and Puppet Crimes then Exhibition House for Crimes of War and Aggression, to finally to the War Remnants Museum.

While the title has changed, the museum still contains a very lopsided view of the war with a lot of propaganda pictures and language. To be clear, there wasn’t much in the museum that was new to me or that wasn’t true, but it was presented in a way that made it seem that the Viet Cong were the kind and gracious people pitted against the blackened, evil hearts of the Americans. In reality, war is an equal opportunity monster-maker.

Most of the museum are graphic photo exhibition rooms. The first room shows pictures of demonstrations and protests from a lot of different countries in the world – more than I had imagined, and some I wouldn’t have even thought would have been so concerned. Like India and Algeria. They even show the resistance in the US, including the self-immolators. Other exhibitions show American war crimes, including the My Lai incident, where several hundred unarmed Vietnamese civilians were killed by a company of American soldiers.

As we made our way up the stairs to the next exhibition room, I knew this one would be the toughest. From the glass windows, I could see a glowing orange halo. And I knew – this was the room dedicated to Agent Orange. Agent Orange was a toxic chemical agent that was used by the Americans during the war to wipe out the jungle foliage. What wasn’t understood fully at the time, is that it causes horrible birth defects. And not just first generation – this stuff is like barbed wire on your DNA and can be passed down through the generations. Three generations later, many Vietnamese are still dealing with the effects of this potent chemical.

Picture after picture of cruelly deformed babies, kids, and adults patterned the walls. I was sickened and moved heavily throughout the room. The large formaldehyde container of deformed fetuses almost put me over the edge. The same type of feelings I remembered having at Dachau concentration camp in Germany and reminded myself why we visit these types of places: to confront reality, to pay respects, and to learn from mistakes.

We exited that room and took a deep breath, regathering our feelings into some semblance of order. The next exhibit was dedicated to war journalists from around the world, and was easily my favorite simply due to its balanced, realistic, and often very expressive view of the war. Many of the iconic photographs were there like the Pulitzer prize winning photographs of the naked napalm girl taken by AP photographer Nick Ut and the Saigon execution by Eddie Adams. However, there were many more photographs that gave startlingly raw insight into what daily life was like fighting the war. Here is a link that gives a good round up of the photographs. I spent a lot of time in this room. It should also be mentioned that many of these journalists didn’t survive the war as many of the captions on the photographs read ‘last photograph.’

Needless to say, this was a somber day for us. Even as I write this post, I’m still processing all my thoughts and emotions from the day. I’m glad to have seen a different perspective, however unbalanced, on this controversial war, and not for reaching any final conclusion, but for sincerely broadening my understanding of it.

Food

In addition to the war aspect, I was also very excited to experience the food aspect of Vietnam. The heavy feelings we experienced were only concentrated in the Củ Chi tunnels and War Remnants Museum. We did not experience any weird feelings elsewhere, and were warmly smiled at just about everywhere we went in Vietnam.

Our guide directed us to one of the best pho spots in Saigon, Pho Hoa. And it did not disappoint. Pho is one of my all-time favorite foods, especially on a rainy day. As it happened, it did rain that day which made the bowl of pho that much more enjoyable. My first authentic bowl of pho on a rainy Saigon day was the best pick me up. To boot, Shiv, previously a poo-poo-er of pho, has slowly taken a liking to it. Win for me!

1 Comment

[…] of Huế is entirely unrecognized in the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City, which gives you a sense of the bias I spoke about […]